News

Exercise and Upper Respiratory Tract Infection (URTI) – To rest or play?

- June 21, 2018

- Posted by: Epworth Website

- Category: News

“Doc, I’m not feeling well today, I’ve got a bit of cold. Should I go to training?”.

This is a question I get asked commonly working with athletes at both the elite and sub-elite levels. To train and/or compete during an URTI is one of the many challenges faced by both the sportsperson and sport and exercise physician. In this article, I will discuss what happens to our immune system during exercise, highlight some of the current literature surrounding this topic and share some practical tips I commonly use in my practice when faced with this dilemma.

What happens to our immune system during exercise?

During exercise, we switch from nose breathing to mouth breathing. This may result in increased deposition of harmful particles in the lower respiratory tract. It also causes the mucosa (lining of the respiratory tract) to dry out, which in turn slows down ciliary movement (a mechanism for clearing harmful bugs) and makes the lining more sticky1. Immediately after moderate to high intensity exercise lasting less than one hour, there is an increase in our virus fighting cell count and cell activity2,3. However, these fall below pre-exercise levels within the first two hours following high intensity exercise2,3. While there is also an increase in other immune cells during acute moderate physical activity, these too temporarily decrease following bouts of intense physical activity3,4. This brief period of immunosuppression after acute intense physical activity results in an immunological “open window” whereby a sports person may be more susceptible to infection1-4.

What evidence is there on this topic?

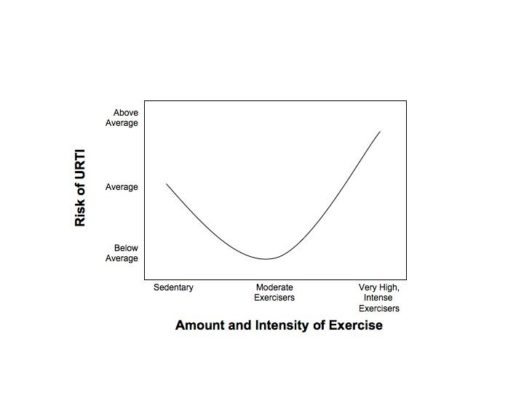

While the results are conflicting, there is some evidence that intense training is associated with higher levels of infection4,5. Nieman has proposed the J-curve, which hypothesises that regular moderate intensity exercise decreases the risk of URTI’s compared to sedentary individuals, while strenuous intense exercise increases the risk of URTI’s (Fig 1)6.

Several papers support the Nieman J-curve hypothesis that moderate, frequent aerobic exercise lowers one’s risk of developing an URTI, while bouts of strenuous, high intensity exercise may increase ones risk7-11. Other studies looking at elite swimmers and long distance runners failed to show any clinically significant correlation between load, intensity and related illness12,13. The exact frequency, duration, type and intensity of exercise required to optimally reduce or increase ones risk of infection is yet to be determined5. Performing intense exercise during an infection has been associated with increased risk of heat exhaustion, post-viral fatigue syndrome and viral heart inflammation14-17. There is no evidence that exercise will affect the duration or severity of an URTI in fit and healthy people18,7.

Will my performance be affected if I play/train/compete with an URTI?

Infection is commonly used to explain poor athletic performance. Infection may compromise optimal muscle function. Exercising when ill also requires greater effort from our heart and lungs, which in theory may result in reduced performance or work capacity5. In one study, elite long and middle distance runners reported a higher perceived training intensity while ill, however there were no objective measurements to back this up. Another study in elite swimmers did not show any meaningful drop off in performance during competition in those with an URTI in the month leading up to competition19. Another study in elite swimmers reported that although, on average, the harmful effects of training while ill was trivial to small, the chances of harm to individuals was significant20.

Practical Tips

- Susceptibility to infection is multifactorial. Determinants such as genetics, nutritional status, rapid weight loss, overtraining, sleep quality, concurrent illness, certain medications, smoking and alcohol consumption may all contribute to an individual’s susceptibility to infection.

- Not all sore throats / runny noses are a simple, short-lived, self-limiting viral infection. There may be other causes of these symptoms that require assessment and treatment by a qualified medical practitioner.

- Anyone with general malaise / fatigue, temperature >380C or resting heart rate >10 beats per minute above normal should avoid athletic activity until these parameters normalise

- In a diagnosed viral URTI, if symptoms are ONLY above the neck (runny nose, nasal congestion, sore throat), an athlete may commence training at half intensity for 10 minutes. If symptoms do not worsen, then training may continue as tolerated at mild-moderate intensity up to 80% intensity

- Modified training may involve more emphasis on skills rather than aerobic / endurance training

- If there are symptoms below the neck and/or systemic symptoms (fever, fatigue, muscle aches, severe cough, diarrhoea / vomiting) then an athlete is not recommended to train

- Always practice good hand hygiene before and after using communal exercise equipment and at meals. This may be either with soapy water or antiseptic hand gels. Athletes should avoid sharing drink bottles.

- Regular, moderate intensity physical activity may not only be good for our immune system, but is also important in the prevention and management of many chronic diseases such as osteoarthritis, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Always consult with a qualified physician before starting a new exercise program.

Happy exercising!

Dr Brett Frenkiel

References

- Shepard RJ, Shek PN (1999). Exercise, immunity and susceptibility to infection. A J-shaped relationship? Phys Sports Med. 27(6): 47-71

- Woods, et al (1999). Exercise and cellular immune function. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 31:57-66

- Nieman D (1999). Nutrition, exercise and immune system function. Clin sports med. 18:537-48

- Metz (2003). Upper respiratory tract infections: who plays, who sits? Curr Sports med Rep. 2:84-90

- Brukner P, Khan K (2012). Clinical Sports medicine, 4th Edition.

- Nieman D (2000). Is infection risk linked to exercise workload? Med Sci Sports Excer. 32(7):406-11

- Nieman et al (2010). Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults. Br J Sports Med. Sep;45(12):987-92.

- Neto et al (2011). Importance of exercise immunology in health promotion. Amino Acids. Nov;41(5):1165-72.

- Moreira et al (2009). Does exercise increase the risk of upper respiratory tract infections? Br Med Bull. 90:111-31.

- Murphy et al (2008). Exercise stress increases susceptibility to influenza infection Brain Behav Immun. 22(8):1152-5

- Matthews et al (2002). Moderate to vigorous physical activity and risk of upper-respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 34(8):1242-8.

- Fricker et al (2005). Influence of training loads on patterns of illness in elite distance runners. Clin J sports med. 15(4):246-52

- Gleeson et al (2000). Immune status and respiratory illness for elite swimmers during a 12-week training cycle. Int J sports med. 21(4):302-7

- Primos JR (1996). Sports and exercise during acute illness. Recommending the right course for patients. Phys Sportsmed. 24(1):44-54

- Budgett R (1998). Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome. Br J Sports Med. 32:107-10

- Parker and Brukner (1996). Chronic fatigue syndrome and athletes. Sports med train rehab. 6:269-278

- Friman and Wesslen (2000). Infections and exercise in the high-performance athlete. Immunol cell biol. 8:510-22

- Weidner and Schurr (2003). Effect of exercise on upper respiratory tract infections in sedentary subjects. Br J Sports Med. 37:304-6

- Pyne et al (2001). Mucosal immunity, respiratort illness and competitive performance in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 33:348-53

- Pyne et al (2005). Characterising the individual performance responses to mild illnesss in international swimmers. Br J Sports Med. 39(10):752-6